Ian Woodmansey, Pilot for the Altitude Balloon Company in the UK, investigates.

Flying comes so naturally to us today that it seems strange that there ever was a time that Man’s feet were firmly glued to the ground. But it was not so long ago – less than 225 years ago in fact – that the idea of flight was still only a dream for our great great grandfathers.

Humans used to look at the sky and fantasize about gliding high above the earth like the birds. Many of science’s great minds had tried and failed to imagine a way of defying gravity. The famous early English scientist Roger Bacon, a Master at Oxford University, put forward the idea of a flying machine that sounds remarkably like a balloon in the 1200s, when he was considered to be either a genius or a crackpot: "Such a machine must be a large hollow globe of copper or other suitable metal, wrought extremely thin in order to have it as light as possible. It must then be filled with ethereal air or liquid fire and launched . . . . . into the atmosphere, where it will float like a vessel upon the water."

It took another Oxford man, James Sadler, another half a millennium until he finally managed to turn theory into practice and become the first ever flying Englishman.

Sadler (1753–1828) was born in Oxford and was the eldest son of a pastry chef and confectioner with a shop at 84 High Street, and a second in St. Clements. He inherited his father’s business, but his taste was for science, engineering and adventure, not confections, and he found employment working as a laboratory technician in the University’s chemistry laboratory. It was here that he began experimenting with small gas-filled balloons. He became inspired by stories of the first ever manned flight in France in 1783, and was determined that an Englishman should fly at the earliest possibility.

On 4 October 1784 Sadler made the first ascent by any English aeronaut with a 170 foot hot air balloon he had constructed himself. The balloon was rudimentary, to say the least: the fabric of the balloon was made from silk, lined on the inside with paper, and heated by a fire strung under the canopy on an open grille - in the language of the time if was powered by “rarefied air”. He “ascended into the atmosphere” from Christ Church meadow in Oxford and rose to ¾ mile high in this basic and unsafe flying contraption, flew for half an hour and landed 6 miles later near the village of Woodeaton to the north of Oxford. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Sadler's ballooning exploits was that he was ‘sole projector, architect, workman and chymist’ in all his flying experiments.

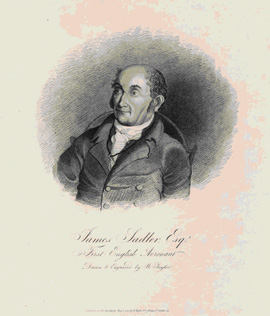

James Sadler Esq., First English Aeronaut, Drawn and Engraved by Benjamin Taylor

(Portrait of Sadler from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Tissandier collection)

Considering the importance of the occasion, the Oxford Journal appeared rather underwhelmed:Oxford Journal, October 4, 1784

Early on Monday Morning the 4th instant, Mr. Sadler of this City, tried the Experiment of his Fire Balloon, raised by means of rarefied air.

The Process of filling the Globe began at three o’clock, and about Half past Five as all was complete, and every Part of the Apparatus entirely adjusted, Mr. Sadler, with Firmness and Intrepidity, ascended into the Atmosphere, and the Weather being calm and serene, he rose from the Earth in a vertical direction to a Height of 3,600 Feet. In his elevated Situation he perceived no Inconvenience; and, being disengaged from all terrestrial Things, he contemplated a most charming distant View.

After floating for near Half an Hour, the machine descended, and at length came down upon a small Eminence betwixt Islip and Wood Eaton, about six Miles from this City.

In the early years of flight the development of the first hot air balloons and gas balloons was happening almost exactly in parallel. They were both first flown for the first time in 1783 in France, and it was soon discovered that gas balloons (lifted by “inflammable air”, later renamed hydrogen) had much greater carrying capacity and endurance. Sadler’s second ascent, just over a month later, was also from Oxford, but this time in a hydrogen balloon. The balloon would have been equipped with a net over the envelope (canopy), onto which was attached a ring from which was suspended a very ornate car, containing a seat for the aeronaut, and the oars with which it was hoped to steer the balloon. The envelope would likely have been made from the gut of an ox, which is a light and very gas-tight material. Numerous ‘guts’ were attached and sealed together to make the spherical envelope.

Sadler generated hydrogen gas in casks containing small pieces of iron with diluted sulphuric acid; and from there it was conducted by pipe into the balloon. After a successful inflation, Sadler took off from the Physic Garden (Botanical Gardens) in central Oxford in the presence of a very large crowd.

He was immediately and rapidly swept over Otmoor and Thame. Seventeen minutes after take-off, he experienced a very rough landing some 20 miles away on the estate of Sir William Lee at Hartwell, near Aylesbury. After dragging for some distance, the balloon blew into a tree and was completely destroyed. Luckily, Sadler escaped injury. Unsurprisingly, exploits such as these turned early aeronauts into popular figures, and their fame spread rapidly throughout Europe. Fuelled by the excitement surrounding early flights in Oxford and London, ballooning became highly fashionable in England. Aeronauts became some of the most talked about celebrities of the day, and tales of their exploits and adventures swept across Britain creating a national mania for the sport.

Sadler made 4 more ascents in 1785, with interesting results. On his second ascent from Manchester in May, he rose to 13,000 ft, travelled 50 miles, and landed or, rather, half-landed at Pontefract. He was badly injured when the balloon dragged him for 2 miles and finally threw him out onto the ground before taking off again empty.

His final flight of the year in October was a nightmare. Caught up in a strong northerly wind, Sadler attempted to land under very difficult conditions at Lichfield. The balloon dragged him across country and battered him about for upwards of 5 miles. Sadler held on for dear life until he finally fell out while the balloon was close to ground --whereupon it immediately shot upwards and was never seen again.

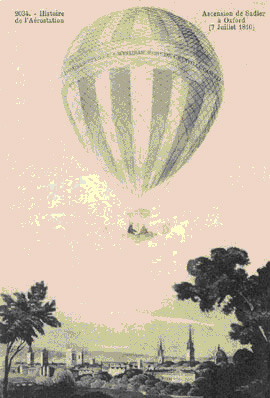

James Sadler over Oxford, 7 July 1810 Clearly, early ballooning involved many risks, and Sadler quickly became a skilful and daring pilot. There were various challenges to piloting man’s first ever flying machines, some related to the flying side and others to human factors. Before take-off pilots had to deal with crowd control issues: inflation was a tedious process and due to leaks in the apparatus it could take much longer than expected. Gathering crowds – who had often paid handsomely to be there - could grow steadily more restless, fearing that they may have been swindled. On at least one occasion it is recorded that, in order to appease an increasingly restive crowd, Sadler risked life and limb by attempting an ascent even though the balloon was not fully inflated.

Following the challenges of take-off, the pilot then had to stop the balloon on the landing field – not an easy task as noted above, especially if flying on a windy day. On October 7th 1811, Sadler set a balloon speed record as a gale swept his balloon 112 miles in eighty minutes. The following account is from The Gentleman’s Magazine: :The Gentleman’s Magazine, October 7, 1811

Mr. Sadler made his 21st ascension from Vauxhall, near Birmingham, with a passenger named Burcham, amidst an immense concourse of spectators. The process of filling the balloon (which was 40 feet high by 50 wide) was completed by two o’clock, and 20 minutes after, it rose rapidly, steering North East by East. In about three minutes, they were enveloped in a cloud, which they soon cleared, when the aeronauts were at a sufficient height to have an extensive view of the surrounding country; Lichfield, Coventry, Tamworth, and Atherstone, appearing nearly under them. At 40 min. past two, the aerial voyagers perceived Leicester bearing East.

In the neighbourhood of Leicester, the wind shifted due East, and in that direction they proceeded towards Lincolnshire, when the aeronauts were at their greatest elevation (about two miles and a half); from thence they saw the towns of Peterborough, Stamford, Wisbeach, Crowland, &c. Mr. Sadler, perceiving a current of air passing under him to the Northward, deemed it prudent to descend, in order to avoid being carried toward the sea. The balloon now quite distended, it became necessary to let out some of the gas, which was done at intervals, till it descended into the current Mr. Sadler had previously noticed; and the adventurers were carried directly Northward. Spalding was now on their right, and Bourn on their left, when they threw out their ballast. The car first struck the earth at Boston, to the Southward of Heckington, with extreme violence, the grappling irons being ineffectually thrown out; and on the second concussion, Mr. Sadler, having hold of the valve-line, was by a sudden jerk, caused by the grapple taking hold for an instant, thrown violently out, and unfortunately received several contusions on the head and body; but, notwithstanding, had sufficient presence of mind to call out to Mr. Burcham not to quit his seat.

The balloon immediately rose, about 100 yards, with great velocity, to the great hazard of the Gentleman who remained in it. At length he succeeded in pressing the bag of rarefied air, sufficiently to occasion the balloon to descend again; and throwing out the grappling-iron, in the parish of Asgarby about a mile and a half from the place where Mr. Sadler was thrown out, it came in contact with a tree, which stopped its progress; and Mr. Burcham was fortunately relieved from his perilous situation, and safely landed with only a slight bruise. The aerial voyage was completed at 40 min. past three, being one hour and 20 min. from the moment of ascension, having in that short space traversed a distance of at least 100 miles. Mr. Sadler lost both his flags; and the balloon was nearly destroyed.

Each aeronaut had believed the other dead, and they were delighted to meet in person at the village of Heckington shortly after their mishap.

As if all this were not enough, even after landing safely balloonists were never quite sure what reception they would receive from the locals, who may well have never seen such a contraption before. This letter, probably from one William Ball, describes what it must have been like:

"Tuesday afternoon last, about four o'clock, an air balloon fell in a field in the parish of Farrington in this county, to the no small consternation of the neighbouring villages, which it passed over at a height of about 40 yards. It fell in a field among a parcel of cows who gathered round it hideous bellowing. The farmer and his men agreed to attack it; seeing it bounding on the ground, they concluded it to be some monster come to carry off the cattle; one of his men, more courageous than the rest, went to it, and secured it by tying it to the railings of a rick. The curiosity of the country for six or eight miles round was never more raised than to see the air balloon".

By such accounts of Sadler’s exploits, he seemed destined for an early grave, but each time he somehow survived and prospered and proved to be the toughest balloonist of his age -- perhaps, of any age.

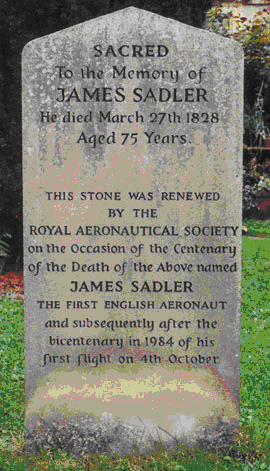

By 1815 Sadler had achieved his forty-seventh ascent, and he moved back to Oxford to live with his family. Against all odds, he died peacefully in his bed aged 75 on 26 March 1828, in George Lane. He was buried four days later at St Peter-in-the-East, Oxford, where he had been baptized.

James Sadler was a man of prodigious talent – a man of practical action, not formal education. Sadler is remembered as one of the pioneers of aeronautical exploration in Britain and his daring flights helped make ballooning a national pastime.

As well as being the first Englishman ever to fly, he was a great experimenter and was among the first to use coal gas to make light. He experimented with driving wheeled carriages using steam engines, and he patented a steam turbine design. Sadler researched copper sheathing of ships, distillation of sea water, seasoning of timber, gunpowder combustion, and constructed air-pumps, signal lights, and apparatus for disengaging oxygen.

He has been honoured in Oxford by a restored gravestone and a plaque, tributes to his pioneering and brave aerial exploits all over Britain and Ireland.

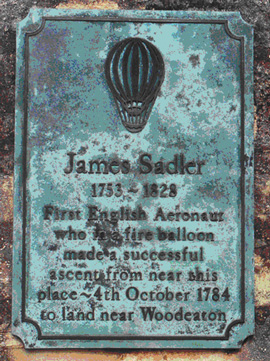

The plaque is on the wall of Merton College in Deadman's Walk (to the side of Christ Church Meadow). It was unveiled by the Lord Mayor of Oxford on the bicentenary of Sadler’s first flight on 4 October 1984. It reads: James Sadler

1753–1828

First English Aeronaut

who in a fire balloon

made a successful

ascent from near this

place — 4th October 1784

to land near Woodeaton

Sadler's grave in St Peter in the East churchyard (now part of St Edmund Hall), which was also restored to mark the bicentenary of his first flight. The burial register gives his address as George Lane, and states that he died at the age of 75 and was buried on 30 March 1828

There are 2 portraits of James Sadler in the National Portrait Gallery, St. Martin’s Place, London.

With thanks to

H. S. Torrens, ‘Sadler, James (bap. 1753, d. 1828)’, first published Sept 2004, 1300 words in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Fishponds Local History Society

And with special thanks to www.printsgeorge.com

|